New Voice Scholars: Perspectives

Transforming Education through Professional Learning

“The New Voice Scholarship is a fabulous opportunity for skilled and motivated educators to be recognised by their peers. ACEL is committed to giving-back to the profession, through the provision of world-class learning opportunities for up-and-coming leaders, and we are thrilled to welcome the 2016 Scholarship winners into the ACEL network. There is also opportunity to have their voices heard through ACEL Publications and at events. All winners of the New Voice Scholarships were invited to write for the special issues of Perspectives, where they consider the following topic, with no limitations or directions, If you were able to transform education (given a metaphorical magic wand), what would you do? These perspectives are, like our New Voice Scholars contexts, diverse and inspiring. I hope these articles challenge and inspire you to reflect further.”

Aasha Murthy, CEO ACEL

Cath Apanah

Assistant Principal

Montrose Bay High, Glenorchy, TAS

Education is a field which requires belief in the power of a growth mindset and aspirational thinking. We nurture these qualities in our students, staff and the communities we serve. Without the ability to believe in our capacity to grow and improve it is almost impossible to be an effective educator and leader.

At the heart of transformation is change, which is deeply rooted in producing and achieving positive outcomes. Real transformation relies heavily on strong leadership and flexibility, for it to deliver on the promise of meaningful change and impact positively on student learning.

My blue sky thinking remains tethered to achievable actions which, with determined leadership, any school could undertake and is in fact reflective of the journey of my current school. Having seen the positive impact it had on my school, I know that it works. My idea to transform education is as complex and simple as supporting leaders to develop and implement a focussed, cohesive and data informed whole school professional learning agenda.

Without a cohesive agenda, schools are at risk of remaining motionless, or worse being pulled in unintended directions when each acts as an individual rather than a cohesive team. Like a sled with a team of huskies at the helm, our teachers are our greatest asset and ally in moving forward. Schools are filled with keen and willing staff who are passionate and have a degree of natural instinct and training. Strong leadership is needed in: setting the course, training staff to improve pedagogy and provide a cohesive language, along with a structure to band the team together so everyone is pulling in the same direction towards the goal. This is transformative because it is not dependent on outside elements to be implemented, but places control squarely in the hands of school leaders, empowering them to engage in conversations about their data and determine an agenda.

At Montrose Bay High, we are on a journey to create an effective professional learning community. We began with a merger when two schools joined together to create a new identity. Our transformation from challenging to award winning school is underpinned and kept on course by our cohesive whole school professional learning agenda. When we feel we are drifting off course we are righted by reflecting on and returning to our agenda.

Each element is essential if there is to be real transformation. It’s not enough to have a professional learning agenda. To be impactful, your professional learning agenda must be: connected to your context, purposeful, and coordinated around a key idea providing structure and direction. There must be cohesion, one connective thread running throughout, ensuring the team is pulling in the desired direction. It must be data-informed and evidence-based, and connected to SMART goals to which teams are accountable and progress is measurable. The agenda must also be applied to the whole school, everyone must be included and held accountable for making an impact.

Key to the success is identifying the centre point of your agenda as well as allocating time. Choosing your focus means making a commitment and agreeing that at every opportunity you will prioritise this agenda. Of course there will be Departmental directives and things which pop up. However, setting the agenda provides stability to both the leadership team and whole staff. Whether your team is large or small, you can never afford false starts as they can squander good will and create confusion. Invest the time to ensure you have a cohesive agenda and that it will work in your context. The agenda must also be valued, prioritised and allocated time. Even with the best intentions, without time built into the timetable, the agenda will fall over. Part of that time must create opportunities for staff to collaborate and work together, as this breaks down barriers and works to embed the desired changes.

I recall striking up a conversation with another teacher at a workshop. When I asked her what she hoped to get out of the workshop her response surprised me. Every teacher at her school had to pick something to attend during the year. She knew this was a nice venue and the summary she read interested her; however, there was no expectation that this workshop should align with school priorities or that she might share her learning with her colleagues. It saddened me because it was evidence of ineffective school leadership and a school without direction. This teacher wasn’t being asked to contribute to the school’s agenda; each teacher was pulling in their own direction. Imagine how much more leverage might have been achieved had this teacher been clear about how her learning connected to her school’s agenda and how she might share it with her colleagues to improve practice and student learning.

Not harnessing the collective power of your staff to generate a positive shift within your school is a wasted opportunity. Teachers are predominantly positive people who work hard to improve the outcomes of their students. If there is a better way of helping students learn we have a duty to explore alternate ways of skilling staff to make that a reality. Developing and implementing a focussed, cohesive and data-informed whole-school professional learning agenda has the capacity to transform education by building and harnessing powerful teams that work together to improve learning outcomes. In doing this, you are once more believing and investing in people’s capacity to grow and improve, which is the ultimate manifestation of transformation.

Perspectives

Alexandre Guedes

Head of Learning

Thomas Carr College, Tarneit, VIC

Rethinking professional development for teachers

There are many wonderful and positive examples in our community of teaching excellence: teachers who have a profound impact on the learning of the students in their classrooms and teachers who instil a love of learning and a sense of wonder in the students with whom they interact. They achieve this by implementing effective pedagogical practices which impact on the outcomes of their students. John Hattie and others have now well established that quality teaching is of paramount importance to the educational outcomes of students and it is important to realise that in our ever changing educational climate teachers must exhibit a love for lifelong learning and continue to build their capacity to meet the multifaceted challenges they face.

The capacity of teachers is a complex blend of attributes that is ever evolving. The skills, knowledge and dispositions that teachers must possess are heavily debated with competing interests at all levels in our community, placing demands on what teachers need in order to function effectively in their role. The research linking professional development programs and teacher capacity is strong and highlights that through the enhancement of teacher knowledge, skills and dispositions we improve classroom teaching and therefore improve outcomes for students but how do we best do this when the community often disagrees on what teachers should know, do and be.

It is unfortunate that there is still a dominant rhetoric of deficiency which paints teacher education and professional development in a very negative light. A rhetoric that perpetuates a model of teacher capacity building centred on mandating hours of professional learning. In addressing mandated hours of perceived ‘weaknesses’ in skills and knowledge, teachers come to see this approach as little more than a ‘tick the boxes’ exercise they must do in order to satisfy the various requirements of teacher registration and educational jurisdictions. The view that professional development is something done to ‘get hours up’ comes from teachers who have witnessed with cynicism the plethora of initiatives that rarely are effectively implemented into classrooms and that result in our current educational landscape of exemplary practices that seem to only take root in a few classrooms and schools.

As an educational community we invest significant resources into the capacity building of teachers through professional development programs which take many forms. Unfortunately the large majority of programs are not school embedded. ‘One-off’ workshop models for example are popular due in large part to their low time requirement yet the research shows us that this is not an effective model with as little as 5% of what teachers learn in ‘one-off’ programs finding its way into classroom practice. Michael Fullan reminds us that implementation of a strategy is far more difficult than learning it. Yet we find that supporting educators in the implementation phase is a rare feature of most professional development programs. It is natural for teachers to try and fail and try again when implementing something new or experimenting with their practice. It is important to realise that there will likely be little or no impact on the classroom teaching where programs lack fundamental support and feedback to educators.

Peter Senge once remarked, ‘learning is dangerous,’ it is a risk for teachers to try something new and to extend their skills in order to improve their practice. When professional learning programs leave teachers isolated and unsupported in their attempts to implement strategies, it should come as no surprise that teachers return to the practices they feel most comfortable with when things do not go so well. In order to support the professional development of educators we need to consider the challenge as a whole, from the learning of strategies through to the implementation of them in the classroom, and we must incorporate the evaluation of these programs in relation to the promises they make.

The teachers who work in our schools are hardworking professionals who derive so much of their drive and motivation from the interactions they have with the students in their classroom. The research of Thomas Guskey and others shows that there is little evidence to support the rhetoric that professional development must be about ‘fixing teachers’. On the contrary there are amazing exemplary teachers working in very trying circumstances who want to develop their skills and knowledge in the best way they can. With the attrition rate in teaching estimated in some studies to be as high as one in four, rethinking how we support and value capacity building must be a key consideration in supporting teachers to face various challenges in schools.

The capacity of educators is crucial to the outcomes of students in their classrooms. We must do better to support educators in growing their capacity. To do so we must advocate for and promote professional development which support teachers and raises the esteem of the profession. Countless dollars are spent towards professional development, yet we rarely evaluate the effect that these programs have in the classroom and in the large majority of cases we leave teachers without support in the implementation of strategies.

Lifelong learning is a key attribute of our profession and we must exhibit this to our students and the wider community as we keep abreast of new knowledge, develop our skills and challenge our conceptions on learning. Unfortunately, there are many cases of teachers who quite rightly feel cynical about the current way professional development ‘fads’ come and go, especially when they see little impact on the learning of their students and it seems that the next ‘promised’ silver bullet to solve all the educational issues is just around the corner. We must provide a system of support to ensure the professional learning of teachers is embedded and leads to improvement in practice.

Perspectives

Amanda Heffernan

Lecturer

Lecturer

University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD

We can transform education by taking control of the narrative surrounding schooling today. As a profession, we have the collective power to enact this change. The current narrative around schooling frequently reinforces the notion that we’re failing, or falling behind other countries. This can be seen in news reporting on slipping ‘standards’, our politicians focusing on ‘teacher quality’ as a cure-all, and the intense focus on measurable school improvement in our education systems.

Some agree with the focus on measurement of certain types of achievement, and others, myself included, question the implication that measurable achievement via PISA and NAPLAN testing is the principal way to determine a school’s (or a school system’s) effectiveness. Regardless of our personal beliefs, this narrative of failure works to position education in particular ways. The negativity associated with these judgments impacts upon student experiences of schooling and, in the words of one principal, “can grind you down, fiercely”.

Transforming the Narrative for Educators and School Leaders

Research into principals’ leadership has highlighted for me just how constrained and disempowered many of our school leaders and teachers can feel in the current climate of education.

Principals have told me that autonomy is outweighed by heavy external accountabilities. While the rhetoric is that principals can and should make decisions based on their local needs, in actuality they are being governed by data, guided from a distance to focus on certain elements of education because of public pressure with each release of NAPLAN results. Research has identified concerns about the resulting narrowing of educational focus to that which will directly impact on testing results. Redefining the education narrative to move beyond these notions of achievement may provide principals with the power to focus on their school needs beyond testing results, knowing there is a public understanding that there is more to school than these aspects of education. Certainly, many principals are already doing this, but it is undeniable that our school leaders and teachers are feeling pressured by these accountabilities, and may be adjusting their practices as a result.

Collectively defining the purpose of schooling, and focusing on more than just testing results, may also help empower teachers to address some of the concerns that have been raised in recent years about the direction of schooling. Evidence tells us that the emphasis on standardised testing may actually diminish student achievement and that teachers may feel constrained in their planning and teaching. Anecdotally, teaching colleagues have told me that they feel the goal of instilling a love of learning in children has been lost. Redefining the narrative around schooling could begin to help redress this.

Transforming the Narrative for Students

When the education narrative is so heavily focused on measurement of student achievement, it’s easy to think this is the purpose of schooling. It goes without saying that we all want our students to succeed and to achieve their goals. However, the focus on measurement and the associated pressures on students has reached a point where students exposed to high stakes testing are experiencing anxiety and are being told from the early years that they are failing to meet benchmarks and targets. Concerns have been raised that an overemphasis on these facets of education could fall short of providing students with a holistic understanding of the world around them, including meeting the goals of the Melbourne Declaration to create ‘active and informed citizens’.

As a society, we need to have a shared understanding of the purpose of schooling. Is it to prepare students for jobs or to be competitive in a global marketplace? If so, then perhaps the continued focus on literacy and numeracy in accompaniment with testing is appropriate. It must be noted that this focus has been identified as narrowing the curriculum and placing less emphasis or focus on creativity, the arts, and the humanities. Evidence suggests that students who have specific learning needs might disengage and lose confidence in themselves in these testing environments. Therefore, if we do decide that our key focus is producing the next generation of workers, then we need to ensure we meet the needs of these students.

Alternatively, is the purpose of schooling about creating global citizens who love learning, who want to attend school and engage with their communities? Does schooling need to educate for a holistic world understanding and empathy so that our students – the leaders of the future - can address some of the issues we’re seeing in the world today? Can a test or measurable achievement ever really tell us whether students have these qualities?

Thus, the narrative around the purpose of schooling matters, and it matters a lot. Collectively defining why we do what we do is the first step in allowing educators to take control of the narrative and engage in these discussions in meaningful and constructive ways.

How might we do this?

As a profession, regardless of whether we are early childhood, primary, secondary, or higher education teachers, we can unite to amplify our voices. We can share the positive stories each day to help reframe discussions about the realities of schooling. Our teaching associations and unions can use their voices to promote the best of what we do. If the media reports on our successes as often as our challenges, a shift could take place in the way our communities see our schools and our profession. We know there is no quick-fix or easy solution to the challenges facing schooling today. Giving the experts - educators and education researchers - an opportunity to participate in policy development is key in ensuring we work towards a schooling system that is representative of what we value in education.

This recalibration of our story and our purpose as educators can begin to address some of the complex issues impacting upon our students by enabling us to move beyond the easily measurable. I believe this narrative change is within our grasp if we can raise our voices as a profession.

Perspectives

Catherine Scott-Jones

NT Department of Education

NT Department of Education

Arnhem Division, NT

Ground up, community driven educational reform

The future of Education needs to evolve from the ground up and be contextualised to the many and varied school communities across Australia. ‘One size fits all’ approaches, mandates by systems and politically motivated, personality and top-down driven change agendas, are stalling educational reform. School staff are exhausted with constant change and the increasing demands that strip them of the opportunity to reflect, innovate and deliver quality education to their students. Systems invest millions in new programs or strategies in attempts to quickly remedy gaps rather than supporting school communities to collaboratively prescribe the changes needed that will meet the needs of all students. Embracing and implementing a Continuous School Improvement framework will enable schools and regions to use data, engage staff and have filters on school improvement decisions so that all of the school processes and programs implemented in the school will help the school achieve its mission according to their context.

Schools essentially have to work smarter, not harder and see themselves as organisations that personalise its business to serve the students, families and the community where they are placed. Schools that actively seek to understand how well they are doing in providing what families and the community value and believe, makes a difference to their children and seek feedback on how to improve the school, will be better placed to target school processes that will meet the needs of their clientele. Therefore, as an alternative to cluttering and exhausting schools with a myriad of add-on programs and strategies that may or may not close gaps, schools need to: take time to honestly review multiple measures of data, measure and evaluate their programs and processes, problem solve using evidence-based knowledge and locally understood best practice, to make decisions and plan based on a shared mission and vision. This alternative will help schools and systems to be proactive and forward-moving in school improvement, informed by their own data, with decisions filtered by what matters most to the school community. This approach allows schools and systems to push back on those things that do not make an impact on learning.

Giving schools the space, opportunity and support to develop and drive their own continuous school improvement and reform agendas, based on what they know, value and believe, will make a difference for all learners in their school will contribute to individual freedom, empowerment and community development. Education is a fundamental human right for all students. UNESCO promotes the “right of every person to enjoy access to education of good quality, without discrimination or exclusion.” In Indigenous Education, community members, for too long, have been marginalised in school decision-making and rarely, if ever, been asked what they think and feel about the school and their relationship to the school or how it could be improved. While visiting school staff come and go, community members remain hoping that the next new leader and their way of ‘doing school’ will engage their kids. Indigenous education outcomes for remote schools cannot improve significantly until strong partnerships are established that empower the communities to own the mission and vision, and develop and lead their local school to improved outcomes for their children.

In the Northern Territory, 72% of schools are remote or very remote with the many of these schools located ‘on country’ in Indigenous communities. In an effort to transform education from the ground up, Arnhem and Palmerston and Rural Regions in the NT Department of Education (NT DoE) have embraced Victoria Bernhardt’s Continuous School Improvement (CSI) framework as a tool to improve school and regional decision-making. The evidence-based framework has been developed and refined from over two decades of collaborative work with schools and systems through Education for the Future, a not-for-profit organisation, where Victoria Bernhardt is the Director. Bradley Geise, from Education for the Future has been supporting regions and schools in Arnhem, Palmerston and Rural Region since 2011 when Arnhem Region initiated Continuous School Improvement work across their region.

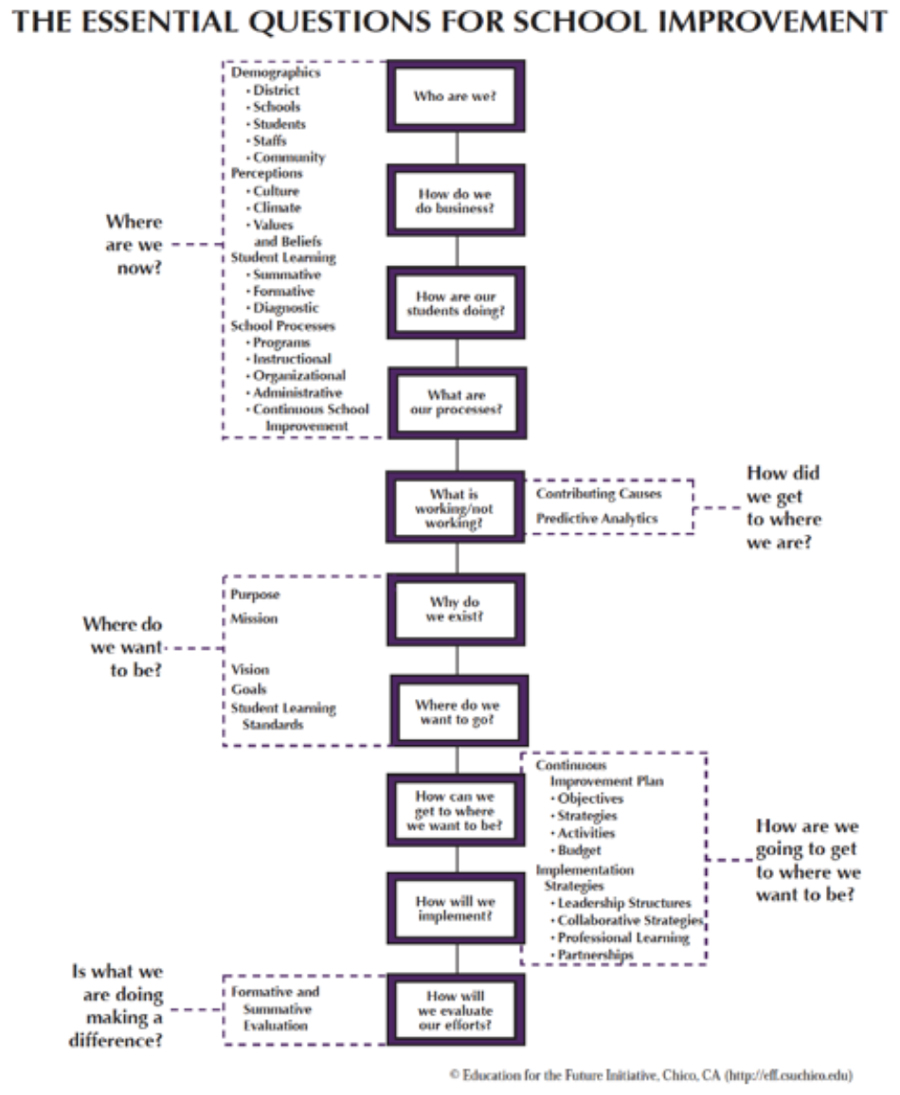

Figure 1. Continuous School Improvement Framework (Bernhardt, 2013)

The Continuous School Improvement framework, represented in Figure 1 is outlined in Victoria Bernhardt’s book, Data Analysis for Continuous School Improvement 3rd Ed (2013). Support can be accessed through Education for the Future to assist educational organisations to use the framework for continuous school improvement. The framework’s strength is in empowering the key change agents with data so that they can collaboratively prescribe the change that is required, to fulfil the mission and shared vision of the school.

This ground up approach enables schools and systems to work collaboratively as a whole school community. It promotes a process where everyone’s voice is valued and data and best practice is understood by all in the community and is used to inform a school community owned mission, vision and continuous school improvement plan. This framework is inclusive of faith development, cultural identity or other things valued by the school community. The development of the mission and shared vision is essential in this process to empower and transform educational organisations to meet the needs of all of their students.

Schools need to make their own informed decisions about what they value and believe will make a difference for all learners. A collaboratively developed mission states the core purpose of the school, and a corresponding shared vision articulates what is needed to achieve the mission relative to curriculum, instruction, assessment, and environment.

(Bradley Geise, Education for the Future, 2016)

The challenge for school leadership is to successfully transform a school’s mission and vision into action by inspiring, leading, developing and managing people and the processes whilst also acting as mediators between school–system–community. This type of school transformation must involve all relevant key stakeholders and staff and be supported by the system with data gathering and sharing of evidence-based practice and providing structures that enable schools and teachers more time and space to innovate and develop as educators through professional learning communities. Importantly, using this framework requires that educational leaders move away from top-down and personality driven decision making, towards facilitation of ground up collaborative development of schools and systems as appropriate to their context with the school community.

Using a ground up approach such as the Continuous School Improvement Framework (Bernhardt, 2013) can transform education in Australia by moving schools and regions from being schools and regions of compliance, to ones of commitment where the key change agents support and implement with fidelity the processes and programs that they believe will lead to the results and outcomes that the school community desire. Education systems and schools need to understand what these outcomes are and what families and communities define as success for their children. Only then can we craft the kind of education and schools that will reform education in Australia, resulting in all students learning and succeeding and communities empowered and transformed.

References

Bernhardt, V. L. (2013). Data Analysis for Continuous School Improvement 3rd Ed. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education.

Bernhardt, V.L. (2013). The Essential Questions for School Improvement. Chico, CA: Education for the Future Initiative.

UNESCO. (2016) Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/right2education

Perspectives

Jacques Du Toit

Head of Humanities & Business Studies

Head of Humanities & Business Studies

Riverside Christian College, QLD

Educators need to become modern learners and take charge of their own Professional Learning by embracing connected learning environments and changing mindsets.

The need for educators to become modern learners requires a fundamental adjustment in the way educators approach their professional development. The nature of technological advancement, ubiquitous access to information, and changing digital environments will require educators to change to better serve a student cohort that require a different skill set compared to previous generations. New technologies and social media are driving changes in information and learning. Wismarth (2013) explains that there is a move away from the traditional lecture-by-expert model of instruction towards a 21st century pedagogy of collaboration, and this demands a concurrent shift in the role and attitudes of the educator. This new dynamic society requires innovative uses of technology, and a much greater emphasis on collaboration (Ball & Forzani, 2009). Thomas and Seely Brown (2011) contend that “information is also a networked resource, engaging with information becomes a cultural and social process of engaging with the constantly changing world around us”.

George Couros (2014) puts it, “One of the hardest things to do in education is to not change others, but to change ourselves.” Tom Whitby’s (2015) point that “the gap between teacher and student will continue to widen if the educator’s’ mindset for learning does not evolve”, further strengthens the idea that educators need to change. The educators themselves are the key to any changes that are required, and this needs to be addressed by focusing on changing existing professional development to a more networked, collaborative, and self-directed model. Time is the most precious commodity for educators, and this is why having the right professional development is key to creating educators with 21st-century skills. Lieberman & Pointer-Mace (2009) explain that professional development, though well intentioned, to be fragmented, disconnected, and irrelevant to the real problems teachers face. Many countries have already provided educators opportunities to collaborate as part of their working days, and it provides greater opportunity for learning to take place with colleagues (Lieberman & Pointer-Mace, 2009). Carroll (2005), agrees that education “requires leadership commitment to change the culture of the school to support regular, sustained, ongoing collaboration among teachers, principals, and students.” Creating opportunities for teachers to collaborate through time allowance is crucial, but also utilising digital tools to extend this to a wider network is even more important.

An area that Professional Development would need to focus on is not just on training educators how to use technological tools, but understanding the when and why. Educators will need to know how to model the uses of technology or explicitly teach their students about the technologies and their uses. The access to new media tools and social networking provide a means for networked learning to scale up, and thus creation of personalised learning networks. The idea that most people learn in “communities of practice” is key with regards to the concept of connecting through collaboration. When changing traditional professional development to allow the development of new learning skills, the creation of a Personal Learning Network (PLN), becomes essential. A PLN consists of a network of individuals that all contribute in some form to the development of an individual, whether virtually or in-person. Will Richardson (2007) explains that, ‘everyone’s network will look different’ and Buchanan (2011) notes, “at the heart of a PLN are people… from whom you can learn and with whom you, in turn, can share and converse.” (p. 19). At the core of a PLN is relationships, and how we support one another.

A PLN requires interaction and participation, as it grows and changes over time to reflect individual requirements and interests. Connectivism allows educators to understand that knowledge can be obtained through valuing the diversity of opinion and is at the core of a successful PLN. A PLN blurs the line of conventional professional development and creates informal learning opportunities. The learning is ongoing, recognises the role of the individual organising their own learning and that it takes place in multiple contexts with an online PLN. Aaron Davis (2014) provides this great analogy on being connected, “as sitting at a bar drinking pedagogical cocktails where we can mix different ingredients to come up with our own flavours.” It becomes a very personalised, organic and ever-changing network that contributes through sharing knowledge and learning. It is a movement towards learning all the time and everywhere, and this creates a new paradigm for learning and growth. The terms lifelong, life-wide, or self-directed learning all point to our ability to continuously learn and grow. As George Couros (2014) puts it, “Can you imagine when a teacher gets really excited about their learning, the difference that makes on their students?

Connected learning is social and personal, and as such, every network is unique and cannot be reproduced exactly the same. Each educator will need to discover and nurture their personal learning network to fully realise its potential to transform their own learning and skills. Personal learning networks are shifting the balance from institutional professional development to learning with the world. With technology as the enabler and the individual as the director, there can be a complete transformation in educators taking charge of their own professional learning.

References

Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of teacher education, 60(5), 497-511.

Buchanan, R. (2011). Developing a personal learning network (PLN). [online].Scan, 30(4), 19-22; Retrieved from http://search.informit.com.au.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/fullText;dn=189317;res=AEIPT

Carroll, T. G. (2005). Induction of Teachers into 21 st Century Learning Communities: Creating the Next Generation of Educational Practice.The New Educator, 1(3), 199–204. doi: 10.1080/15476880590966934

Couros, G. (2014a, December 30) Fresh Eyes. [Blog Post]. Retrieved from http://georgecouros.ca/blog/archives/4985

Couros, G. (2014b, November 8). The “Want” and the “Way” [Blog Post]. Retrieved from http://georgecouros.ca/blog/archives/4881

Davis, A. (2014, July 21). Becoming a Connected Educator - #TL21C Reboot [Blog Post]. Retrieved from http://readwriterespond.com/?p=37https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiGabUBQEnM

Lieberman, A., & Mace, D. P. (2009). Making Practice Public: Teacher Learning in the 21st Century.

Thomas, D., & Brown, J. S. (2011). A new culture of learning: Cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change, Lexington, KY: CreateSpace.http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/934354596?accountid=10344

Whitby, T. (2015, January 26). Why Twitter Will Never Connect All Educators [Blog Post]. Retrieved, from https://tomwhitby.wordpress.com/2015/01/26/why-twitter-will-never-connect-all-educators/

Wismath, S. L. (2013). Shifting the Teacher-Learner Paradigm: Teaching for the 21st Century. College Teaching, 61(3), 88–89. doi:10.1080/87567555.2012.752338